YES, YOU CAN GIVE 2 VOTES TO ONE CANDIDATE.

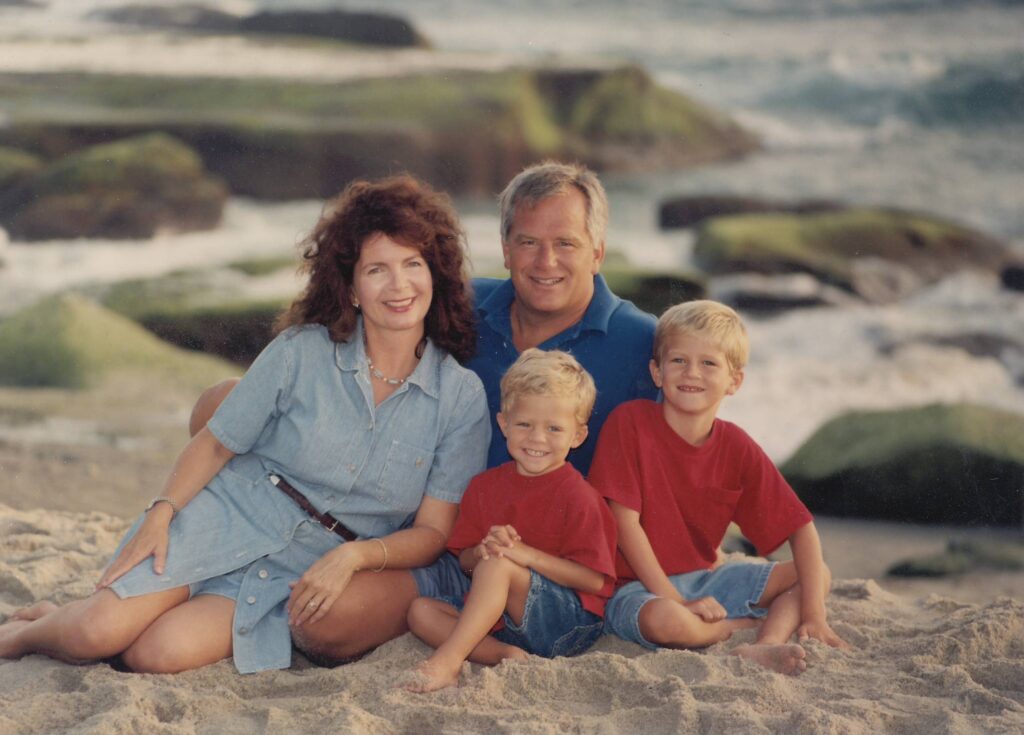

I have lived in Beacon Hill for just over 30 years. Married with 2 boys, now ages 30 and 33. I am retired from teaching Algebra and Geometry at Niguel Hills Middle School. You know the classes that students love.

I enjoy solving problems. I am running for a position on the Board of Directors for the Master Association to address many concerns.

Beacon Hill is a beautiful and valued community but has room for improvement.

Concerned about the loss of views over the last 30 years.

Concerned about several homeowners who have had issues before the board of directors for over a year that the BOD has failed to mediate to a solution.

Concerned that 3 of 5 current board members were hand selected and appointed rather than elected by membership at some point.

Concerned that HOA meetings are held by Zoom on Wednesdays at noon which are difficult for many to attend. The lack of in-person meetings does not allow dialogue with members and Board of Directors.

Concerned about the 2 pending lawsuits by homeowners against the Master Association which I think could have been avoided.

Concerned about the lack of obtaining competitive bids for many projects.

Concerned about common areas that need attention. Example: HOA walls that need painting, etc.

Concerned that some Board members treat homeowners with disrespect.

Concerned that the Board of Directors, past and present, have not followed rules, regulations, and due process, and giving some homeowners preferential treatment.

Concerned by the lack of transparency from the Board of Directors.

Concerned that HOA polices and/or procedures encourages neighbors to report on each other, potentially leading to strained relationships between neighbors. This type of situation creates unnecessary tension and conflict between neighbors within the Beacon Hill community.

Concerned that homeowners are frustrated when they believe their homeowners association (HOA) are not responsive to their concerns, leading them to seek legal assistance.

Concerned that posted HOA Zoom minutes often do not reflect what transpired at the Zoom meetings and minutes are sometimes not posted in a timelier manner.

Concerned that the NEW indemnity clause provides that a homeowner, who in good faith follows all the rules, submits a proper application with professional architectural plans…that the HOA in their judgement approves…have to indemnify the HOA for THEIR decision.

Concerned about the tree policy which has homeowners pay for trees that obstruct their view to be removed.

I promise to work toward addressing these concerns, and any others that come to my attention. I will look for win-win outcomes and work with homeowners to solve HOA related problems.

I would appreciate your vote and support for change and a better Beacon Hill.

YES, YOU CAN GIVE 2 VOTES TO ONE CANDIDATE.

I would appreciate your support and vote.

Your neighbor,

Mike Erickson

Update.

I have had much feedback in the last week or so from phone calls, emails, texts and out in the community. Many positive comments and responses. One person was almost in tears describing trying to get help from the HOA.

Not everyone can attend zoom meeting on a Wednesday at noon.

It was suggested that I have an email for members who wish to support these concer

ns.

So, if you have a concern or suggestion, please contact me at abetterbeaconhill@gmail.com

REMEMBER THAT I NEED TO BE ELECTED TO ADDRESS THESE CONCERNS.